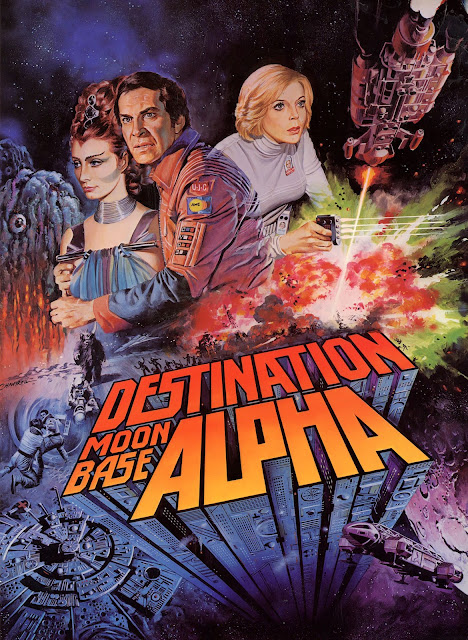

SPACE: 1999.

Over the Christmas holiday, I’ve become reacquainted with Gerry and Sylvia Anderson’s lavish science fiction series, which starred (then) husband and wife actors Martin Landau and Barbara Bain. In 1975-76, it was like watching 2001: A Space Odyssey every week. Courtesy of my dad I’d seen that when I was five so, for me, cosmic existentialism every Saturday afternoon was just the ticket.

Before Star Wars (1977) changed everything, Stanley Kubrick’s majestic if ponderous epic was the benchmark for serious, philosophical science fiction. Consequently, in 1970s TV and film SF, space was portrayed as a dangerous, disturbing and often surreal place, and Space: 1999 captures that fear of the unknown perfectly. The series’ production values were also off the scale. At the time, it was the most expensive production ever made for British television, and still stands as a hi-tech, high concept vision of the near future, an honourable companion piece to Kubrick’s cold, clinical masterpiece.

The premise of Space 1999 is both bold and crazy: the moon is blasted out of Earth orbit by a nuclear explosion and propelled on an odyssey through deep space. The marooned personnel of Moonbase Alpha are constantly searching for a planet to settle on, encountering a variety of alien friends and foes along the way. Throughout the series, it’s suggested that the Alphans are central to the destiny of the universe and may even have some divine protection…

That said, I’ve always favored the Andersons’ UFO over Space: 1999. The former was an exciting mixture of James Bondery, psychological weirdness, modish fashion and stunning modelwork. Yet Space: 1999 retains the same air of psychedelic strangeness as its 1970 predecessor. Consider the howling, tentacled horror in ‘Dragon’s Domain’; the futuristic ghost story ‘The Troubled Spirit’ (which scared the living shit out of me when I was a child); the shock cannibalism of ‘Mission of the Darians’; the surreal, Kubrickian journey through a ‘Black Sun’; Peter Bowles’ nihilistic, indestructible psychopath Balor in ‘End of Eternity’… there are many other striking examples. At the same time, there were exemplary visual effects sequences like the space battles in ‘War Games’; Gwent, the gigantic spacecraft in ‘The Infernal Machine’, silently rolling across the lunar surface, and the onslaught of missiles against armoured gun platforms in ‘The Last Enemy’. And no one does an explosion like the Andersons.

The so-called permissive society of the 1960s had made its mark on UFO, and the same was true of Space: 1999. For instance, when Joan Collins’ character Kara is introduced in ‘Mission of the Darians’, it’s via her legs. The camera lingers on her limbs, as well as on the hem of her pink minidress, which is so short it barely conceals the tops of her thighs. The scene is borderline pornographic even by today’s standards.

Thankfully, in the lead role of Commander John Koenig, Martin Landau is wonderfully intense, committed and subtle. In the scene in ‘Collision Course’ in which an alien reveals to him humanity’s destiny, you can really see the pride and awe flickering in his eyes. Landau is all the more impressive because he conveys such emotion without speaking or moving.

The inventive directors on Space: 1999

range from Ealing Studios legend Charles Crichton to The Sweeney’s gritty

auteur Tom Clegg, while composer Barry Gray’s musical cues are so distinctive

you find yourself daydreaming that you’re watching one of the Andersons’

Supermarionation shows – Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons (1967-68) or Joe

90 (1968-69), perhaps. However, Gray’s easily recognizable house style only

adds to the enjoyment.

As you might have guessed by now, my favourite episode of the first season is ‘The Troubled Spirit’ (above). Johnny Byrne’s taut script is astonishingly well directed by Ray Austin (the stunt coordinator on The Avengers in another life.) The episode begins with a virtuoso tracking shot away from a guitarist and his audience, down a moonbase corridor, to a séance in a hydrponic lab. The guitar playing becomes more and more frantic as things start to go wrong, image and soundtrack dovetailing beautifully to heighten the tension. This duality continues throughout ‘The Troubled Spirit’ as Dan Mateo (Giancarlo Prete) is haunted by a disfigured spectre, sitar-like guitar chords in turn haunting the soundtrack. The twist ending is a chilling masterstroke.

With a change of producers in its second year – Sylvia Anderson was out, Fred Freiberger, who’d produced the third season of Star Trek over 1968-69, was in – Space: 1999 would take a controversial creative swerve. But that’s a discussion for another time…

Comments

Post a Comment